A Portrait of a Graduate identifies the traits we want for our students, but it remains just a vision without intentional pathways within our educational system. Student experiences reveal what a system truly values. Consider the student who revises a major project three times and finally demonstrates proficiency, only to receive a C because early drafts were averaged in. The message is clear: our promise to value growth doesn’t align with how we measure learning. As one insightful student told me, while our vision emphasized the journey, our grading practices still rewarded the race. Students adapt to what is actually measured, not what is merely displayed.

When Vision Meets Practice

A portrait comes alive when it flows through curriculum, instruction, culture, and grading practices. Too often, these conversations happen separately. One team focuses on collaboration, creative problem-solving, and continuous growth, while another averages points, applies penalties for late work, and sorts students by percentage. These disconnected practices send students a very different message from the one the portrait promises.

Effective implementation requires recognizing the difference in scale between Portrait competencies and traditional academic standards. Portrait competencies—such as Critical Thinker or Resilient Learner—are broad outcomes developed through authentic application. Academic standards can be nested within these competencies, providing contexts in which students practice and demonstrate the skills.

The Adult Commitment

Closing these gaps requires more than policy changes; it demands that adults embody what we’re asking of students. The Portrait of a Graduate is more than a description of student outcomes; it’s a commitment adults make to model the traits we expect students to develop.

- If graduates should be thoughtful communicators, educators must cultivate communication, and leaders must model it.

- If graduates should take intellectual risks, adults must behave in ways that make risk-taking safe.

- If graduates should be curious and critical thinkers, leaders cannot default to compliance-driven decision-making.

When adults model these attributes, the portrait doesn’t just describe the student experience; it defines the adult culture of the system as well.

Two Approaches to Adult Alignment

Systems approach adult alignment in two ways. Some create parallel portraits with role-specific traits. Others unpack the same portrait for different stakeholders. Neither is inherently better. The choice depends on your context and how your community thinks about shared accountability.

Aligned but Separate Portraits

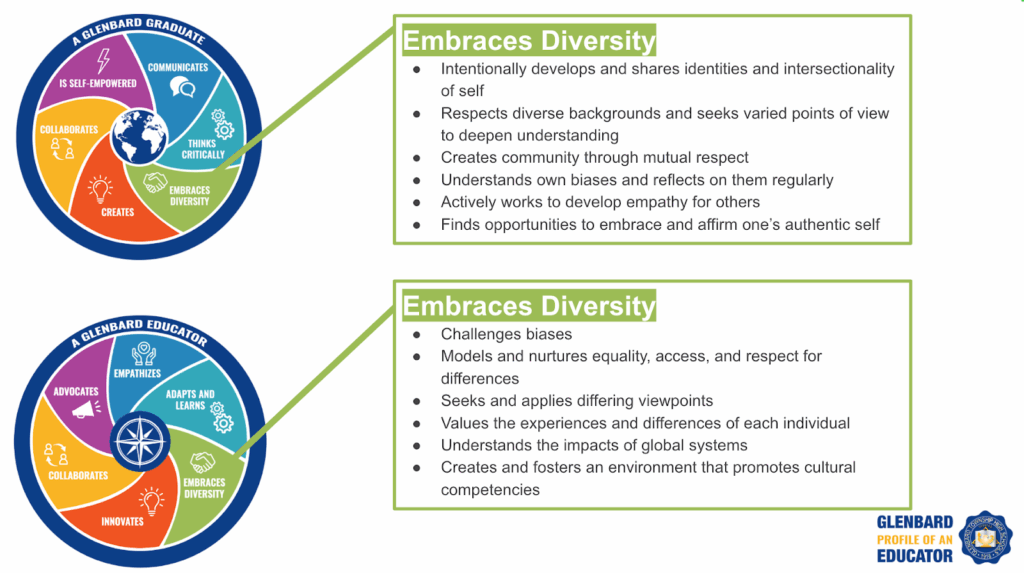

In this approach, some traits are consistent, and some vary by role but remain aligned. Glenbard Township High Schools in Glen Ellyn, Illinois created distinct portraits:

| Glenbard Graduate | Glenbard Educator |

| Is Self Empowered | Advocates |

| Practices responsible decision-making and considers impact on othersCreates, monitors and reflects upon ambitious and realistic goals Builds and sustains strong, healthy relationships Advocates for self and others in a socially responsible, empathetic mannerEmploys a growth mindset that includes self-regulation, motivation, and resiliency | Cultivates a sense of voice, ownership, and agency for each studentGuides students to identify barriers, develop plans, and take actionCollaborates with stakeholders to promote educational policies and strategies for the benefit of all studentsHelps students to access resources and strategies |

Aligned Portraits for Students and Adults

Some systems may choose to unpack the Portrait of a Graduate and embrace these traits as areas of focus for all stakeholders.

Here’s how focus areas might be personalized by role:

| Graduate Expectation | Educator Expectations | Leader Expectations |

| Effective Communicator | Educators model strong communication and create structured opportunities for students to practice it. | Leaders communicate clearly and invite honest dialogue, listening actively to staff, students, and families. |

| Critical Thinker | Educators design tasks that encourage inquiry, exploration, and complex thinking. | Leaders make decisions by examining evidence, considering multiple perspectives, and encouraging a culture of questioning. |

| Resilient Learner | Educators create environments where students can take academic risks, learn from mistakes, and try again. | Leaders create psychological safety for staff so adults can try new approaches, learn from challenges, and continue growing. |

| Globally Aware Citizen | Educators design learning experiences that engage students with diverse cultures and perspectives. | Leaders advance inclusion through policy and create authentic opportunities for students and adults to practice global awareness. |

Glenbard chose separate-but-aligned portraits to honor the distinct responsibilities of educators while maintaining coherence. Other districts may decide on unified portraits to emphasize that everyone, students, teachers, leaders, and families, shares the same aspirational portrait traits. In Goose Creek CISD, leaders and learners share collaboration, communication, and leadership as key traits shared by all stakeholders.

The key is intentionality. Whichever approach you choose, make explicit how adults will practice what students are expected to learn.

What a Living Portrait Looks Like

You can tell a portrait is alive when:

- Educators use transparent, outcome-based evidence to measure learning

- Learners receive feedback that supports reflection and revision

- Leaders model the same skills they expect educators to cultivate

- Policies emphasize growth rather than compliance

- Families can read a grade and understand the story of learning behind it

This is what coherence looks like. It’s when the portrait stops being a poster and becomes the practice.

Making the Promise Real

The Portrait of a Graduate is ultimately a promise. It is a commitment that our systems will develop specific traits in every student. That promise becomes real when we align our daily practices with our shared values. When grading reflects growth, when leaders model risk-taking, when policies prioritize learning over sorting, the portrait stops being aspirational and becomes the lived culture of your system.

Where to Start: A Design Process for Alignment

Closing the gap between vision and practice requires the same iterative approach we ask of learners—observation, experimentation, reflection, and revision. Whether you frame this as design thinking or Plan-Do-Study-Act cycles, the pathway is similar:

Observe and Notice

Begin by making the invisible visible. Where do your current practices contradict your portrait? This might be grading practices that penalize early attempts despite valuing resilience, or professional learning structures that require compliance when you espouse innovation. Spend time noticing patterns: What messages do students receive about what really matters? What do families understand from report cards? What behaviors do your policies actually reward?

Empathize and Engage

Invite the voices most affected by these practices—students, educators, families—into the conversation. Their lived experiences reveal misalignments that adults might miss. Having students at the table while you co-design to transform your system supports a revisit of common but conflicting protocols and practices. Ask: How does this practice feel to those experiencing it? What does it communicate about our values?

Determine Readiness and Start Small

Assess your group’s commitment and capacity. Transforming entire systems overnight is neither realistic nor sustainable. Choose one high-leverage practice area and ideate possible changes. Design a small experiment: What would it look like to grade differently in one unit? To restructure one professional learning session? To revise one policy?

Test, Study, and Adapt

Implement your experiment and gather feedback. What’s working? What’s creating new challenges? What are students, educators, and families noticing? Use this data to refine your approach before scaling. This is the “Do-Study-Act” of PDSA—trying, learning, and adjusting based on what you discover.

Iterate With Courage

Coherence doesn’t require perfection. It requires honest reflection and the courage to revise our practices as relentlessly as we ask students to revise their work. Each cycle of observation and adjustment brings your system closer to alignment, making the portrait less aspirational and more lived.

This is the promise we make to every graduate as they leave our learning system and the journey we model as the adults guiding them.

The post A Graduate Portrait Names What We Value. Our Learning System Shows That We Mean It. appeared first on Getting Smart.